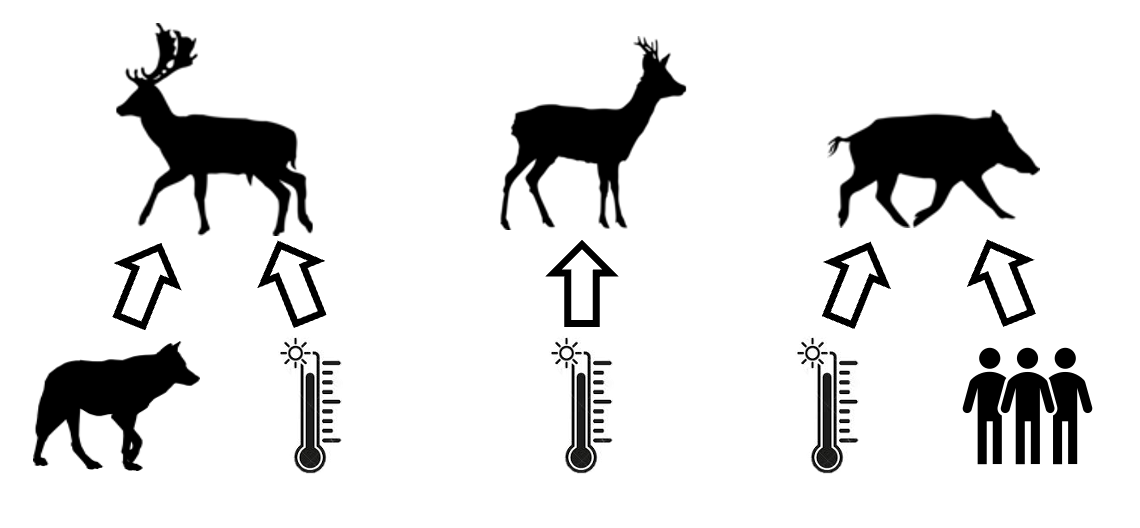

Temperature

All the species in this study reduced their diel activity with the increase of ambient temperatures, showing a degree of thermal intolerance. Furthermore, roe deer and wild boar increased their nocturnality and this could be related to reduced costs of thermoregulation at night. However, at the same time, a reduction of general activity during the hottest days might also diminish the daily amount of time spent in foraging, which may be retrieved during night hours. This could be especially important for income breeders, like roe deer, which rely heavily on the intake of high-quality food for reproduction and lactation.

Wolves

Results suggest a spatial association between roe deer and wild boar with the predator. These results are consistent with most reports of wolf food habits which show that wild boar and roe deer are often the most used prey in areas where they occur. Moreover, the wolf is an opportunistic predator, leading to a higher use of the prey with a greater encounter rate.

The negative relation found between fallow deer nocturnality and wolf detection rate suggests a temporal avoidance. The fact that fallow deer are more diurnal in areas with more predators shows a crucial behaviour effect of the wolf over this ungulate species.

Humans

Wild boar showed a stronger response to the detection of humans, compared to increasing temperatures, by increasing their nocturnality. Indeed, different studies recorded a change of activity patterns towards nighttime for wild boar populations close to human activities and infrastructures. Therefore, in addition to previous studies, also these results seem to suggest a stronger influence of humans on this species.

Conversely, roe deer showed a reduction of nocturnality with a greater number of human detection in the areas. This result must be carefully analysed, as it is weak and close to the threshold. For this reason, other influencing variables such as intra-individual spatial preferences may influence the outcome of this analysis.

Elevation

A negative relationship was found between fallow deer activity and elevation. This result could find an explanation by examining the spatial distribution of this species in the Tuscany region. Fallow deer were predominantly recorded in the coastal area, thus a reduction of their detection rate may not reflect an actual effect of elevation over this species’ activity level.

Conversely, wild boar had a positive relation between elevation and nocturnality. Higher elevations may be correlated with higher activity levels due to a greater daily spatial range. At higher elevations, the daily movement ranges of wild boar are greater due to the possible shorter vegetation period and worst condition of food supplies. So, other factors masked by elevation might elicit nocturnality. Nevertheless, it could still be possible that wild boar at higher elevations are more negatively affected by temperatures. This could be related to the elevation-dependent warming assessing a systematic variance in warming according to increasing elevation. Meaning that higher elevations undergo stronger and quicker effects linked to increasing temperature, and this might affect more wild boar that lives at higher elevations compared to their conspecifics at lower altitudes.

Shrub cover

Roe deer increased their diurnal activity with an increase of shrub cover. Predation rates of wolves over this species has been shown to decrease with an augment of vegetative cover. Therefore, roe deer might use areas with high shrub coverage as an anti-predator response. Moreover, during the lactation period (i.e., summer months), female roe deer select denser habitat to provide successful hiding spots for their offspring.

Fallow deer, on the other hand, reduced their overall activity with the increase of shrub cover. Shrub might limit visibility, thus reducing the potential to detect predators and the effectiveness of vigilant behaviour. Accordingly, fallow deer might perceive areas with dense shrub cover as relatively risky, contrarily to what was said for the roe deer.

DISCLAIMER:

This study analyses the temperatures of 2021, 2022, and 2023. However, global warming does not seem to halt and these ungulate species may face greater temperatures in the future, accompanied by reduced rainfalls, lower water and food accessibility, and a greater risk of heat stress. Therefore, it should be keep into account that the results assessed in this study could change.

References:

Andersen, R., Gaillard, J.M., Linnell, J.D., & Duncan, P. (2000). Factors affecting maternal care in an income breeder, the European roe deer. Journal of Animal Ecology, 69, 672-682.

Beniston, M., Diaz, H.F., & Bradley, R.S. (1997). Climatic change at high elevation sites: an overview. ClimaticChange, 36, 233-251.

Bongi, P., Ciuti, S., Grignolio, S., Del Frate, M., Simi, S., Gandelli, D., & Apollonio, M. (2008). Anti‐predator behaviour, space use and habitat selection in female roe deer during the fawning season in a wolf area. Journal of Zoology, 276, 242-251.

Brivio, F., Apollonio, M., Anderwald, P., Filli, F., Bassano, B., Bertolucci, C., & Grignolio, S. (2024). Seeking temporal refugia to heat stress: increasing nocturnal activity despite predation risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 291, 20231587.

Esattore, B., Rossi, A.C., Bazzoni, F., Riggio, C., Oliveira, R., Leggiero, I., & Ferretti, F. (2023). Same place, different time, head up: Multiple antipredator responses to a recolonizing apex predator. Current Zoology, 69, 703-717.

Johann, F., Handschuh, M., Linderoth, P., Dormann, C.F., & Arnold, J. (2020). Adaptation of wild boar (Sus scrofa) activity in a human-dominated landscape. BMC ecology, 20, 1-14.

Johann, F., Handschuh, M., Linderoth, P., Heurich, M., Dormann, C. F., & Arnold, J. (2020). Variability of daily space use in wild boar Sus scrofa. Wildlife Biology, 2020, 1-12.

Levy, O., Dayan, T., Porter, W.P., & Kronfeld‐Schor, N. (2019). Time and ecological resilience: can diurnal animals compensate for climate change by shifting to nocturnal activity? Ecological Monographs, 89, e01334.

Lionello, P. & Scarascia, L. (2018). The relation between climate change in the Mediterranean region and global warming. Regional Environmental Change, 18, 1481-1493.

Mattioli, L., Capitani, C., Avanzinelli, E., Bertelli, I., Gazzola, A., & Apollonio, M. (2004). Predation by wolves (Canis lupus) on roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in north-eastern Apennine, Italy. Journal of Zoology, 264, 249-258.

Mattioli, L., Capitani, C., Gazzola, A., Scandura, M., & Apollonio, M. (2011). Prey selection and dietary response by wolves in a high-density multi-species ungulate community. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 57, 909-922.

Mori, E., Benatti, L., Lovari, S., & Ferretti, F. (2017). What does the wild boar mean to the wolf? European Journal of Wildlife Research, 63, 1-5.

Pfleiderer, P., Schleussner, C.F., Kornhuber, K., & Coumou, D. (2019). Summer weather becomes more persistent in a 2 °C world. Nature Climate Change, 9, 666–671.

Pepin, N.C., Arnone, E., Gobiet, A., Haslinger, K., Kotlarski, S., Notarnicola, C., Palazzi, E., Seibert, P., Serafin, S., Schöner, W., Terzago, S., Thornton, J.M., Vuille, M., & Adler, C. (2022). Climate changes and their elevational patterns in the mountains of the world. Reviews of Geophysics, 60, e2020RG000730.

Podgórski, T., Baś, G., Jędrzejewska, B., Sönnichsen, L., Śnieżko, S., Jędrzejewski, W., & Okarma, H. (2013). Spatiotemporal behavioral plasticity of wild boar (Sus scrofa) under contrasting conditions of human pressure: primeval forest and metropolitan area. Journal of Mammalogy, 94, 109-119.

Rossa, M., Lovari, S., & Ferretti, F. (2021). Spatiotemporal patterns of wolf, mesocarnivores and prey in a Mediterranean area. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 75, 1-13.

Semenzato, P., Cagnacci, F., Ossi, F., Eccel, E., Morellet, N., Hewison, A.M., Sturaro, E., & Ramanzin, M. (2021). Behavioural heat‐stress compensation in a cold‐adapted ungulate: Forage‐mediated responses to warming Alpine summers. Ecology Letters, 24, 1556-1568.

Spiegel, O., Leu, S.T., Bull, C.M., & Sih, A. (2017). What’s your move? Movement as a link between personality and spatial dynamics in animal populations. Ecology letters, 20, 3-18.